Hapkido Theories of Motion

Most martial arts place an emphasis on two or three areas of technique. Hapkido is somewhat unique as it integrates most aspects of the martial arts, internal arts, and healing arts at different levels of training. This is due to several reasons. First, martial arts have been many different things. In modern times, most emphasize the sport side of the martial arts. Second, few arts encompass the ancient use of ki in their art. This is sometimes, but not always, due to the recent development of new technique for the purposes of competition. Hapkido competition would be too dangerous to be practical. Hapkido is a defense art and a ki art, something once common and now rare; in addition; many of the 3864 techniques practiced in hapkido, are 1400 years old; these techniques have been proven in battle, time and time again over the ages.

Hapkido practice requires two partners who take turns being the attacker (kongyoksa) and the defender (makisa). In dynamic form, the makisa first moves off the line of attack (by either turning or entering) and then redirects the kongyoksa energy and motion. When attacking, one commits the energy and balance in one direction. The hapkidoin moves around the point of conflict and exploits the vulnerabilities of kongyoksa.

When asked to define the term self defense, most people have trouble with putting this concept into words. The dictionary defines self-defense as: self-defense n. 1) Defense of oneself when physically attacked. 2) Defense of what belongs to oneself, as one's works or reputation. 3) The right to protect oneself against violence or threatened violence with whatever force or means is reasonably necessary. But these define an action, not the actual concept of self-defense.

Self-defense as a concept is defined as an extension of self-control. This is based on the premise that you do not have control over someone else’s action, but you do have total control over your own. You determine your reaction to conflict. No one can make you angry without your consent. You determine your destiny and are responsible for where you are and what you do. It is easy and very tempting to blame others and circumstances for your situation, although in reality, there is no one else to blame.

Muscle Memory

You do not have time to think about a response when defending yourself. You can only rely on reflexes, a generic term for muscle memory. In order for the body to respond, the body and the mind must be relaxed. A natural instinct for an individual who does not practice the techniques of self-defense is to panic. This reflex tenses the mind and body. The goal of the hapkidoin is to practice technique to the point that the technique and the three theories of basic motion are embedded into muscle memory.

Our goal in mudo is to keep the body relaxed and the mind calmed so that we can respond through muscle memory. Muscle memory does not pick a specific technique when responding to a self-defense situation. There is no need to memorize specific techniques against specific attacks. Hapkido techniques are interchangeable. Our goal is to flow from the attack to a technique using the attackers directional force. Any technique can be used against any attack. Yes, some techniques do work better against certain attacks, as this is due to the natural flow of the techniques. Continuous practice develops muscle memory.

Muscle memory will happen naturally, it only takes practice. 1500 times with a partner, 1500 times with your eyes closed, and 1500 times without a partner perfecting the detail.

Theories of Basic Motion

1) Balance break

2) Decreasing radius circle

3) Lowing the center

Hapkido basic motion can be divided into three parts, or "theories of basic motion"; 'balance break' (blending; breakaway, or capturing and at a more advanced level, entering or turning), a 'decreasing radius circle' (the transition; technique) and 'lowing the center' (completion; locking and pinning, throwing, or breaking). Blending is harmony, and harmony is a state in which people are working in alignment by blending, we dissipate the force of the attack and harness our power and that of the attacker. Hapkido is a dynamic art; although, in the early stages of training you may practice by setting up the kan (proper distance) and moving from static sogi (stances) and grabs, but the idea is to take active command of any attack. All hapkido techniques can be used while standing, seated, or on the ground. In addition, the techniques are effective in empty hand against weapons application and in weapon against weapon situation.

Entering and Turning

Entering involves entering into an attack instead of standing there to receive it or stepping backward to block or defend it. To the uninitiated it appears that the hapkidoin is evading the attack. While not being hit has a number of benefits for your defense, what entering really represents is the opportunity to blend with an opponent’s attack, leaving the opponent with nothing to strike. Instinct and experience teach us to freeze or slightly better, to move back from a punch or a kick. Instinct never tells us to move into an attack. The very notion of doing so is counter intuitive to our experience. And that is why it is so effective. The timing of entering is also missed at lower levels of training. Entering movement is most effective if it occurs at the same time of your opponent’s attack. Your attacker is expecting you to be where he is striking, not coming towards them. This combination of an opponent’s attacking momentum met with forward movement allows for great speed and ‘surprising’ force.

Turning is a 180 degree pivot to the side or rear of the attacker. Depending upon which foot is forward in sogi, the pivot is either clockwise or counter-clockwise. A rapid turn to the “blind” side of your opponent places you at an advantage for executing defensive techniques. Further, the turn itself allows you to blend with the attack and translate the forward movement of your opponent into rotational force generating power from your hips. As with entering, turning movement is most effective if it occurs at the same time of your opponent’s attack. However, before turning, one enters slightly to create a simple blend and a connection of the centers and works well for getting out of the line of attack.

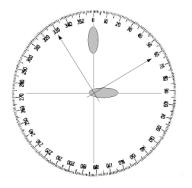

30 Degree Theory

In this picture we can identify the 8 major points of the compass as shown in black. 30-degree theory, for the beginning student, is the movement of direction in direct relationship to your opponent’s center in techniques such as locking and pinning techniques and throwing techniques. It is the movement of direction from your center when performing circular kicking and leg techniques. For the advanced student, one moves 30 degrees away from all 8 points of the compass as shown in the colored lines. This includes both sides of the angle. As sogi (stances) are not passive, but active dynamic moves through the technique, we are always moving our center through the technique applicable to the movement of the elements associated with the directional forces of the associated sogi.

Circular motion (decreasing radius circle) goes hand in hand with 30 the degree theory. When moving linearly motion is at 30 degrees. We move in a circle to dissipate the attack of linear strength.

Ki Son

Son sallyo (ki son ki hand). Good hapkido technique is based on knowledge of how the body responds to certain movements and degrees of pressure. It is easy to see that relaxed shoulders and slightly bent arms generate more power than tight shoulders and stiffly extended arms, and that the economical use of physical power goes a long way. In another form of physiological hapki, son sallyo (simply spreading the fingers widely when grabbed) makes it easier to control an attack. Yet another form is pyungsul (ki strikes). This kind of blow is delivered with the entire hand. Hapkido includes a number of techniques that function on the pulley principle. Simply put, a pulley can change both the direction and the amount of a force, using the principle of zero resistance. With even a small revolution, a pulley can make it possible to move a large object. Similarly when an opponent grabs your wrist you move another part of your arm (for instance, the elbow), so that rather than moving the wrist you use it as a "fixed pulley" and present a strong counter. If the opponent pushes or pulls, or has a very strong grip, a larger circular motion of the body (known as dollyo or turning) is effective in applying the principles of non-resistance to and redirection of a force. This extension of the fingers and the hand also allows the wrist bones to open creating a opportunity for use in choking and throwing techniques at a basic level. In simple practical terms, when an opponent holds your wrist, spread your fingers with a certain amount of force, but keep the rest of your arm relaxed. If your entire arm is stiff you cannot react to sudden pushes and pulls. In short, keep calm and relaxed and abandon all use of ineffective force. This is true son sallyo.

Ki Sonkarak

Ki sonkarak (ki finger). A basic concept in hapkido performed by extending your ki finger in the direction of your movement when grabbing your opponent. Direction is found in a three-dimensional decreasing radius circle movement known as the second theory of basic motion. This also keeps us from relying on strength, but teaches us to rely on technique. Pressure is also added to a technique with the knuckle at the base of the ki finger. Power and speed do not come from themselves, but come from the practice of perfect detailed technique.

Yu (Theory of Flowing Water)

![]() In

Hapkido practice, one does not stop an attacker's force directly

with force, but redirects it. If one will imagine a stream flowing

rapidly down a mountain, the problems to overcome if one decided to

change the direction of the water flow becomes apparent.

Constructing a dam perpendicular to the flow is obviously not the

solution. However, if one would simply divert its flow, success

would be realized. Hapkido theory follows the same approach. One

does not stop an attacker's punch by applying force in direct

opposition to the attack. By applying force to the side,

tangentially, the attack can be diverted and less energy expended.

Water never struggles with any object that it encounters. If water

cannot win the contact, it will not conflict. Instead it will join

with its adversary, providing no friction. Although this is a

demonstration of its ability to adapt, it is important to realize

water never changes itself. Softness is another characteristic of

water that relates to the understanding of Hapkido. We must accept

the fact that softness has the capacity to win against hardness. A

tempered steel bar will eventually break under enough stress. Water,

on the other hand, though it may be made to break up, will

invariably join together again.

In

Hapkido practice, one does not stop an attacker's force directly

with force, but redirects it. If one will imagine a stream flowing

rapidly down a mountain, the problems to overcome if one decided to

change the direction of the water flow becomes apparent.

Constructing a dam perpendicular to the flow is obviously not the

solution. However, if one would simply divert its flow, success

would be realized. Hapkido theory follows the same approach. One

does not stop an attacker's punch by applying force in direct

opposition to the attack. By applying force to the side,

tangentially, the attack can be diverted and less energy expended.

Water never struggles with any object that it encounters. If water

cannot win the contact, it will not conflict. Instead it will join

with its adversary, providing no friction. Although this is a

demonstration of its ability to adapt, it is important to realize

water never changes itself. Softness is another characteristic of

water that relates to the understanding of Hapkido. We must accept

the fact that softness has the capacity to win against hardness. A

tempered steel bar will eventually break under enough stress. Water,

on the other hand, though it may be made to break up, will

invariably join together again.

Won (Theory of the Circle)

![]() The circle is an important figure in

hapkido.

In movement it represents smooth flowing motion as opposed

to straight or linear movement. Force is not met with force, rather

it is

redirected away from the defender. The circle also represents that

invisible and ever changing range at which strikes and further out,

kicks will be a danger to the Hapkidoin.

The circle is an important figure in

hapkido.

In movement it represents smooth flowing motion as opposed

to straight or linear movement. Force is not met with force, rather

it is

redirected away from the defender. The circle also represents that

invisible and ever changing range at which strikes and further out,

kicks will be a danger to the Hapkidoin.

Won also represents the circle of life. We start our hapkido life as a white belt beginner. After years of study and progression up the ranks, the student achieves chodan, only to find that they have come the complete circle and are now beginners again. Outside of the dojang, we begin life dependent on others. Often, after living a full life, the circle is completed as we end life again dependent on others.

Wha (Theory of Harmony)

|

|

|